Every commercial piece of software we use comes with an End User License Agreement (EULA), which we all merrily accept without reading. After all, who has time to read a rambling document of barely decipherable legalese that we can’t do anything about anyway? Sometime I do glance through them, and my blood pressure shoots up (the part I like best is where it says “Some states do not allow the exclusion of [bla bla], so the above exclusion may not apply to you”, which essentially says “we will abuse you all the way, but if your state prohibits this we will abuse you a little less”). 🙁

So, I sometimes remember fondly the old (1980’s) Borland No-Nonsense License, which said:

You must treat this software just like a book …

…By saying “just like a book,” Borland means, for example, that this software may be used by any number of people, and may be freely moved from one computer location to another, so long as there is no possibility of it being used at one location while it’s being used at another or on a computer network by more than one user at one location. Just like a book can’t be read by two different people in two different places at the same time, neither can the software be used by two different people in two different places at the same time. [you can find the full text here].

Sensible, isn’t it? And fair, too. An agreement decent people might freely enter, and have respect for (check the sentiment expressed here). Our world needs more of this sort of thing!

Incidentally, the distinction between the Borland style and the one prevalent today – what I call People language vs. Lawyer language – is what inspired my own legal blurb on Possibly Interesting.

Worth a thousand words?

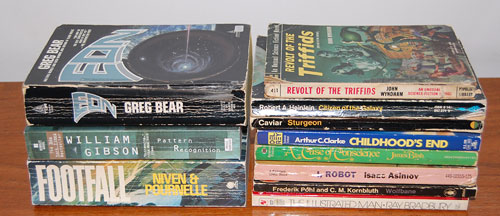

Greg Bear’s hyper-imaginative Sci Fi novel “Eon” brings its protagonists to a parallel reality whose highly advanced post-humans use Picting to communicate; that is, they project in mid-air sequences of holographic icons to convey their thoughts.

This may work for post-humans… but can become a problem when mere mortals try it with excessive zeal. I refer to the increasingly common practice of using pictures and icons in signage and instruction manuals, even when written text would be far better. The notion that pictures are easier to grasp works fine for signs like “left turn” on a road, or “Danger – High Voltage” on a transformer, which are reasonably self-explanatory. And they are invaluable in instruction manuals when they illustrate some technical complexity explained in the text. The problem begins when those manuals start conveying complex concepts like “Don’t drop this camera on a hard floor”, which they might do by showing a person weeping as the camera smashes to pieces…

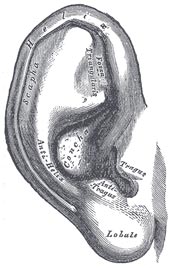

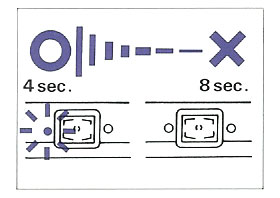

Take this picture, from a Konica camera manual. Can you decipher its meaning? Fortunately the text on the same page explains: it means “The battery should be replaced when the flash takes more than eight seconds to charge”. That’s 15 words, and they are far better than the picture. And from the same manual (this time without a Rosetta stone in the text), the “Don’ts” in this mosaic:

The Thermometer I can get, and maybe the “Don’t take a screwdriver to this camera” (or is it, “Don’t stick a screwdriver in the lens?)… but the one in the center eludes me (“Don’t take photos on windy days”??) and the one to its right is a total mystery (“Beware radiation emanating from TV sets and refrigerators”? Or is that a Microwave oven? And since when do fridges emit anything?)

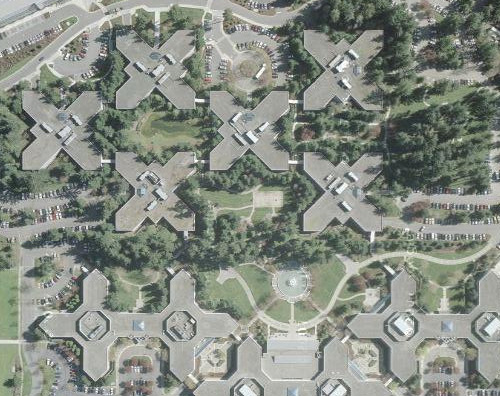

But no manual beats the one we have for our Electrolux dishwasher, which has a pull-out card that starts with exhorting its own virtues (top row, which merely illustrates one word, “RTFM”); then goes on to totally confuse us (is this filter cleanup due daily? Weekly? Daily, but only during the first week of each month?)

And then it shows this masterly rendition of “Help the environment by only using as much detergent as needed”:

Sometimes, I guess, a word (wisely selected) is worth a thousand pictures!