Everyone knows that the QWERTY keyboard layout sucks, because it carries a legacy from the early typewriter days; still, we’re all locked into its use and live in oblivion of what we’re missing. But we have another legacy from mechanical typewriters that is hard to forget because it bites us daily. i REFER TO THE cAPS lOCK KEY.

Everyone knows that the QWERTY keyboard layout sucks, because it carries a legacy from the early typewriter days; still, we’re all locked into its use and live in oblivion of what we’re missing. But we have another legacy from mechanical typewriters that is hard to forget because it bites us daily. i REFER TO THE cAPS lOCK KEY.

It is interesting to trace the history of this design infamy. Originally, it made a lot of sense: in a mechanical typewriter the Shift keys did just that: they shifted the type mechanism vertically so the type bars would hit the paper with the uppercase letters; and the Shift Lock key would keep the keys locked in this position. This key had to sit right above the Shift key, because it physically latched it in a depressed position; hitting Shift again would release the lock. It was very easy to see (and feel) whether Shift was locked or not, because both keys would be depressed when the lock was engaged. The photos below are from an antiquated Royal typewriter; you can see how the Lock key holds down the Shift key on the right (and note the quaint caption on the latter key – Shift / Freedom, in allusion to releasing the Lock).

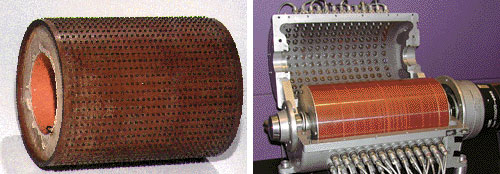

Early computer keyboards carried this idea forward, with a Shift Lock or Caps Lock key that had two physical positions: depressed for Lock, and flush with the other keys when released. You could therefore tell when you were in Caps mode, and would notice immediately if you hit the lock accidentally while touch typing. The delightful Commodore 64 had this feature, among others; the photos show a keyboard that came with the collection of homebrew boards described here, from the late 70s.

Later, as keyboard makers sacrificed quality for cheap manufacturing, the more complex and different two-state key was replaced with a momentary key like all the others, with electronics to implement toggle action. Gone was the tactile feedback. Now a simple brush of the finger could accidentally lock you in Caps mode. Worse still, the position of the Lock key next to the left Shift key, which made sense a century ago, was retained – placing this relatively little used key right in harm’s way.

I don’t see manufacturers giving us back the 2-position key (it would cost them a few cents, after all), but the least they could do is move this stupid key to the top row, next to the Scroll Lock, where it will remain unused, unnoticed, and harmless.

So, what can we do about this? Well, one thing we can do is disable the offending key. No need to tear it out – I used KeyTweak, a free key remapping utility, to disable it on my Windows XP system. Good riddance!

Also, if you use MS Word, you may be unaware that depressing Shift+F3 repeatedly will change any selected text to lowercase, uppercase, and sentence case; a very useful feature after YOU’VE ACCIDENTALLY HIT sHIFT lOCK AND CONTINUED TYPING.

So what, you say?

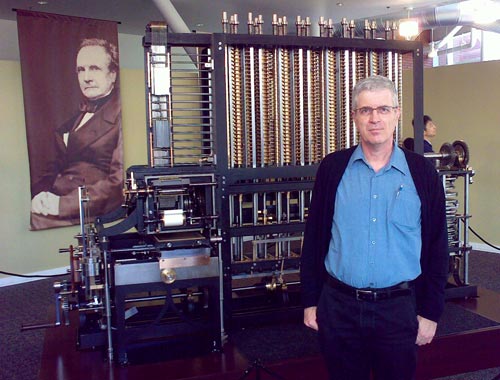

So what, you say? But to the subject of this blog: there was a lecture by Yossi Eliav about The evolution of engineering literacy as seen in Venetian manuscripts about shipbuilding from the 15th century. This mouthful was actually very interesting; but at some point I asked a question about older ships and I was treated to the following insight: these Venetians had large rowing ships (right), galleys, carrying over 100 rowers, which were produced in large numbers and used extensively for centuries; so did the Romans, Carthaginians and Greeks 20 centuries earlier. But the Roman and Greek galleys – triremes, with 3 rows of rowers – were of a completely different, and far superior, construction!

But to the subject of this blog: there was a lecture by Yossi Eliav about The evolution of engineering literacy as seen in Venetian manuscripts about shipbuilding from the 15th century. This mouthful was actually very interesting; but at some point I asked a question about older ships and I was treated to the following insight: these Venetians had large rowing ships (right), galleys, carrying over 100 rowers, which were produced in large numbers and used extensively for centuries; so did the Romans, Carthaginians and Greeks 20 centuries earlier. But the Roman and Greek galleys – triremes, with 3 rows of rowers – were of a completely different, and far superior, construction!

crew them.

crew them.

Everyone knows that the

Everyone knows that the

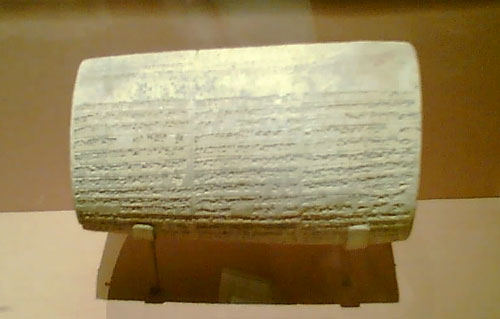

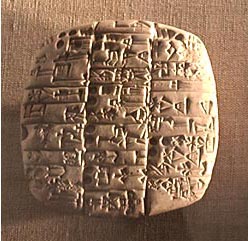

represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!

represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!