Egypt today has its problems, but a few millennia ago the land along the Nile was a center of power, technology and culture. We all know of its monumental achievements in architecture; what is less widely known is that the Egyptians had a very advanced medical knowledge.

So what do you do, if a worker finishing the nose of the sphinx has just dropped his hammer on the head of a coworker down below? Why, you bring the injured guy to a doctor, who then consults his library and comes up with this:

Instructions concerning a gaping wound in his head, penetrating to the bone.

If thou examinest a man having a gaping wound in his head, penetrating to the bone, thou shouldst lay thy hand upon it (and) thou shouldst palpate his wound. If thou findest his skull uninjured, not having a perforation in it…

Thou shouldst say regarding him: “One having a gaping wound in his head. An ailment which I will treat.”

Thou shouldst bind fresh meat upon it the first day; thou shouldst apply for him two strips of linen, and treat afterward with grease, honey, (and) lint every day until he recovers.

As for: “Two strips of linen,” it means two bands of linen which one applies upon the two lips of the gaping wound in order to cause that one join to the other.

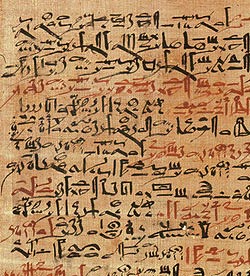

This is Case #2 in the Smith Papyrus, an Egyptian medical treatise from the 17th century BC. It covers 48 cases, from smashed skulls to flesh wounds, each discussed with the same clarity we see above: a title, a description of symptoms, a diagnosis and a treatment course. Not all of them are as easy as the one above; for instance, take Case #6:

Instructions concerning a gaping wound in his head, penetrating to the bone, smashing his skull, (and) rending open the brain of his skull.

If thou examinest a man having a gaping wound in his head, penetrating to the bone, smashing his skull, (and) rending open the brain of his skull, thou shouldst palpate his wound. Shouldst thou find that smash which is in his skull like those corrugations which form in molten copper, (and) something therein throbbing (and) fluttering under thy fingers, like the weak place of an infant’s crown before it becomes whole-when it has happened there is no throbbing (and) fluttering under thy fingers until the brain of his (the patient’s) skull is rent open-(and) he discharges blood from both his nostrils, (and) he suffers with stiffness in his neck…

Thou shouldst say concerning him: “An ailment not to be treated.” . . .

This last does not mean that the guy has no insurance; indeed, the scroll goes on to specify how he will be treated, but only with palliative care, waiting to see if nature will (miraculously) manage.

This last does not mean that the guy has no insurance; indeed, the scroll goes on to specify how he will be treated, but only with palliative care, waiting to see if nature will (miraculously) manage.

Note the incredible degree of diagnostic expertise in this example. Those Egyptians knew their trade all right.

But what I like most about this textbook from another age is how for each case, the doctor must declare the prognosis and articulate his conclusion: “This is X: an ailment which I will treat“, or “This is Y: an ailment not to be treated“. There are even some marginal cases of “an ailment with which I will fight with“.

You can read an early translation of the entire scroll here, or play with an interactive version (with a newer translation) here.

Nice dog, this one: not too ferocious to allow sympathy, yet substantial enough to scare away thieves. And in case your Latin is rusty, CAVE CANEM means exactly what its modern counterpart in the image at right does (but then, Latin being an important influence in English, you could have identified the words in “Caveat” and “Canine”…)

Nice dog, this one: not too ferocious to allow sympathy, yet substantial enough to scare away thieves. And in case your Latin is rusty, CAVE CANEM means exactly what its modern counterpart in the image at right does (but then, Latin being an important influence in English, you could have identified the words in “Caveat” and “Canine”…)

Check the

Check the