Now, I hate litigation, and like many would rather have companies focus on innovating for the greater good; also, I happen to like Android a lot. Nevertheless, I think many criticizers of Apple in its recent victory over Samsung are missing a key point.

The argument goes, Apple sued Samsung for producing smartphones that are rectangular and with rounded corners – how lame is that?!

Yes, that is lame. But Apple also sued about many other alleged infringements, including the application in a handheld device of multi-touch gesture input – the now ubiquitous “pinch to zoom, flick to scroll” kind of user interface that we all love. And that is a whole different story – one that is hardly lame…

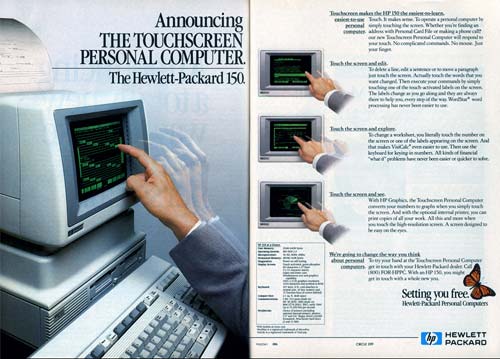

I remember well my first encounter with an iPhone. I remember the feeling of wonder, the ecstasy of experiencing this incredible UI paradigm. It was a revelation, a true revolution, on a par with the first appearance of the mouse-based WIMP interface (which, as an ironic aside, Apple seems to have copied from Xerox for the Lisa and Macintosh computers in the early 80s). It was pure innovation, and with it Apple enabled the very concepts of Mobility and Computing that we all benefit from today.

And that is what Samsung – and Android – had taken from Apple. The overall concept, the basic paradigm, that the iPhone embodies. And yes, I too would have preferred that Apple adopt a more open mind about sharing their technology, but that is not my choice to make. Until they do, let no one say that they’re a bunch of spoiled, un-innovative, litigious whiners suing about the rectangle with round corners. I really think we all do owe them more respect than that!

Photo credit: William Hook under CC license on flickr.

So, here we see a layout that has disappeared without any living descendants: an extinct primordial denizen of the keyboard universe. And for good reason: the standard location puts the arrows nearest the user, where the CompuColor II had them farthest away. It’s bad enough that the mechanical issues of old typewriters forced on us the QWERTY layout, with the most used keys out on the top letter row; since those typewriters did not have arrow keys, there is no reason to apply the same counter-ergonomic approach to them too!

So, here we see a layout that has disappeared without any living descendants: an extinct primordial denizen of the keyboard universe. And for good reason: the standard location puts the arrows nearest the user, where the CompuColor II had them farthest away. It’s bad enough that the mechanical issues of old typewriters forced on us the QWERTY layout, with the most used keys out on the top letter row; since those typewriters did not have arrow keys, there is no reason to apply the same counter-ergonomic approach to them too!

One of the first scientific facts you learn as a child is that snowflakes, those lovely art creations of nature, have a six-fold symmetry. And they do; the properties of water molecules see to that. Hence the standard symbol for snow (and freezing, and cold in general).

One of the first scientific facts you learn as a child is that snowflakes, those lovely art creations of nature, have a six-fold symmetry. And they do; the properties of water molecules see to that. Hence the standard symbol for snow (and freezing, and cold in general).