I recently bought this box of vitamins, and noticed it had a life size outline of the pills’ actual size. This makes sense, since the box is “safety sealed for your protection”, so people can’t see what’s inside before they buy.

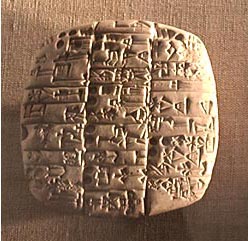

This reminded me (wonders of associative memory!) of something rather different, yet following the same idea, from the History of Computing (one of my favorite hobbies). I read about it long ago, but recently was delighted to run across the real thing in a small showcase in the Pergamon museum in Berlin. Back in ancient Mesopotamia, around 9,000 years ago, people had this neat idea of recording commercial transactions with clay tokens. Different shaped tokens might represent a sheep, a jug of beer, or a sack of grain… and so you could represent a loan or tax payment by a collection of tokens (SAP was far in the future then, as was Excel; in fact they had yet to invent writing, so they couldn’t use that for their records). Here is a sample of these tokens:

Then, around 3,500BC in ancient Sumer, the idea occurred that it’s better to keep all the tokens in an “envelope”, a hollow ball of clay that could be signed with the parties’ seals, then fired to harden it. These balls of clay are like an authenticated, signed record; their content can’t be altered without breaking the ball. The museum had some of these balls cracked open, with the tokens still in them:

And since the clay is not transparent, they would sometimes press the tokens on the outside of the ball before sealing them inside – so you’d know what each ball was about. And now we have an accessible copy of the record on the outside, and a sealed version on the inside… just as with the vitamins box!

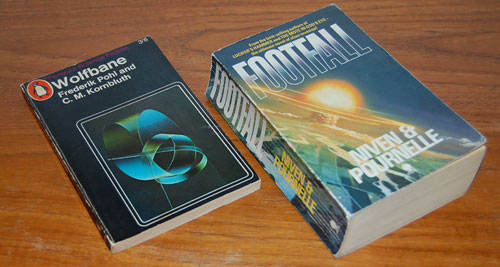

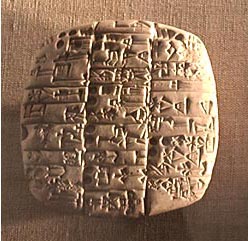

The next step is obvious in retrospect: who needs the tokens on the inside? So around 3,300BC they dispensed with the tokens, flattened the ball into a clay tablet and made do with the indentations on this, as in the next photo.

And lastly… surely you can see where this is going? Once they could  represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!

represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!

More of the science behind this fascinating history can be found on the web site of Prof. Denise Schmandt-Besserat of the university of Texas, a leading researcher of the origins of writing and counting .

I was visiting a hospital, and passed by a seminar room where my eye caught the items in the photo, sitting on a custom stand in the corner.

I was visiting a hospital, and passed by a seminar room where my eye caught the items in the photo, sitting on a custom stand in the corner.

to compete with each other, the different makers dream up the weirdest configurations, with multicolored, contorted handle shapes that remind me of sports shoes (another area where form totally diverges from function in the interest of marketing hype), and with heads that must’ve taken real genius to design. The underlying ideas are impressive – brush heads with multiple bristle types sticking every which way to better remove bacteria from every cranny in the target dentition… all seemingly very important, very convincing, lest the consumer remember that a brush is a brush is a brush, and would work just as well if it had a simple monochrome handle and a straight head. The bacteria wouldn’t mind…

to compete with each other, the different makers dream up the weirdest configurations, with multicolored, contorted handle shapes that remind me of sports shoes (another area where form totally diverges from function in the interest of marketing hype), and with heads that must’ve taken real genius to design. The underlying ideas are impressive – brush heads with multiple bristle types sticking every which way to better remove bacteria from every cranny in the target dentition… all seemingly very important, very convincing, lest the consumer remember that a brush is a brush is a brush, and would work just as well if it had a simple monochrome handle and a straight head. The bacteria wouldn’t mind…

represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!

represent stuff in the real world by abstract marks on a tablet, they were on the path to real writing, starting with pictographs and ending with true cuneiform. Here is another exhibit from the Pergamon, which seems to be halfway through the transition. Wayda go!