A while back I was visiting the wonderful Museum of Business History and Technology in Wilmington, Delaware, which has countless typewriters, that incredible device that will soon be completely forgotten. Among these faithful servants of the authors of yesteryear I saw the device in this photo.

It’s an old Hebrew Remington 92 from around 1930, but what caught my eye was the Hebrew inscription on the frame, which translates literally into “Remington tool of writing type“. Now, the modern Hebrew name for typewriter means literally “writing machine”. And in fact, a little Googling will find you the same old model with this very phrase on it.

So what we’re seeing here is language in the making: the unit in the photo is so early that the term for it hasn’t jelled yet, and different batches were marketed with different names!

Speaking of which, I notice that the name for this machine, in every language I can make out, includes the root “write”, most commonly simply as “writing machine” (machine à écrire, macchina da scrivere, Schreibmaschine, máquina de escribir, etc). Nobody calls it a “printing machine”, even though that’s the immediate action. The important thing is that it is used for writing, in the good old sense that one did with a quill, or a pen, or a pencil, or a piece of chalk. It’s simply an accessory to the creative mind, and all these names – including the discarded one on the Remington 92 above – reflect that fact. Somehow, our computers and keyboards and printers and word processors have lost that linguistic flavor…

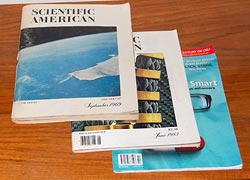

The issues shown are from September 1969, June 1983, and October 2009. The difference in thickness is striking indeed: 10.6, 5.3 and 2.2 millimeters respectively. As far as pages go, the counts are 288, 156 and 72. What happened??

The issues shown are from September 1969, June 1983, and October 2009. The difference in thickness is striking indeed: 10.6, 5.3 and 2.2 millimeters respectively. As far as pages go, the counts are 288, 156 and 72. What happened?? Is this good or bad? Admittedly there’s some attractiveness in ad-free reading; on the other hand, clearly it’s bad for the publisher, and may explain the paucity of real content. It may also explain the cost per page: issue price rose from $1 to $2.50 to $5.99, which is almost constant in normalized present day dollars; but we get less and less pages and articles for this investment.

Is this good or bad? Admittedly there’s some attractiveness in ad-free reading; on the other hand, clearly it’s bad for the publisher, and may explain the paucity of real content. It may also explain the cost per page: issue price rose from $1 to $2.50 to $5.99, which is almost constant in normalized present day dollars; but we get less and less pages and articles for this investment.

Here’s the latest addition to the gallery: I spied this on a piece of medical equipment (a Critikon Dinamap vital signs monitor). It shows a dot centered in a circle for ON, and the same dot banished outside the circle for OFF. Luckily, they weren’t lazy and included the two words as well. This removes the possible confusion I’ve remarked on in my post on the

Here’s the latest addition to the gallery: I spied this on a piece of medical equipment (a Critikon Dinamap vital signs monitor). It shows a dot centered in a circle for ON, and the same dot banished outside the circle for OFF. Luckily, they weren’t lazy and included the two words as well. This removes the possible confusion I’ve remarked on in my post on the

Which made me think for a moment of how far forward – or is it backward? – we’ve come from the days of the simple mirrors still seen on vintage cars, as in the photo at right. In the fifties, a mirror was just that – a round sheet of silvered glass fixed in a round metal plate that pivoted on an arm. That was all – 4-5 parts, max, all externally visible. No innards at all. And cheaper to replace, I’m sure, than the bill the owner of the car in the first photo will face.

Which made me think for a moment of how far forward – or is it backward? – we’ve come from the days of the simple mirrors still seen on vintage cars, as in the photo at right. In the fifties, a mirror was just that – a round sheet of silvered glass fixed in a round metal plate that pivoted on an arm. That was all – 4-5 parts, max, all externally visible. No innards at all. And cheaper to replace, I’m sure, than the bill the owner of the car in the first photo will face. So I was delighted to see

So I was delighted to see

So what, you say?

So what, you say?