Form follows function; but often both must follow the available materials.

Consider the image that comes to mind at a statement like

The great king raised his mighty sword to smite his enemies.

Surely, you imagine a sword structured something like this:

Photo courtesy Søren Niedziella, shared on flickr under CC license.

This, after all, is just about what a proper King’s sword would have to look like to serve him well.

Right?

Well, how about this instead?

Photo courtesy Dbachmann, shared on Wikimedia Commons under CC license.

Would you recognize this as a sword? If you were an Egyptian or Mesopotamian soldier some 4000 years ago, you certainly would. In fact, this was what a standard battle sword looked like between 2000 and 1300 BC. This one, missing its hilt at the right end, is from 1750 BC.

These weapons were in use across the ancient near east, and were called Khopesh in Egyptian. Their only sharpened edge was the outer side of the curved part at the left. You used this edge to beat on people, much like you’d use a club; stabbing was not even an option.

So, what’s going on here? A sword should be long, thin, sharp and pointy, so you can stick it into people at arm’s length; why make one that looks like a short, thick, bent metal rod that can only be used to clobber your enemies?

This is where a key fact comes in: we’re talking Bronze Age, when iron (and much less steel) was unavailable. Weapon designers were constrained by a metal that was too soft for anything long and thin; nor would it stay sharp for long. A one-sided “sickle sword” like the Khopesh could have a thick backside that would give the bronze both durability and hitting momentum.

Over the years the design varied somewhat; notably the sharp part grew longer at the expense of the handle, as in the sword below:

Incidentally, I wasn’t kidding about the king: below you see a PR image of Ramesses III smiting his enemies with a curved sword just like this one. He grabs the smaller-than-life enemies by the hair and is ready to smite them with the sword’s edge (the kings of those days, unlike today’s ornamental ones, were pretty hands-on where smiting was concerned). In fact, this image makes sense of the fact that “smite” is defined in the dictionary as “to strike with a heavy blow or blows” – strike, not skewer as with later sword designs. The guy on the right is more than a king – he is the Akkadian God Nergal, no less, and he holds a sickle sword in his left hand, its blade resting on the ground.

But then came the iron age, and it became possible to craft sharp long blades that wouldn’t break; and the bronze Khopesh went the way of the flint axe, doomed by a new technology that enabled new forms and new functionality.

That’s Progress for you…

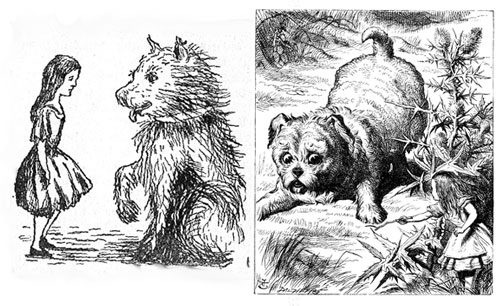

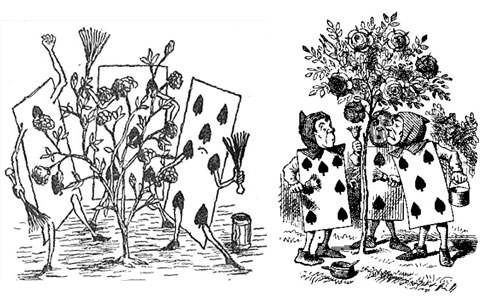

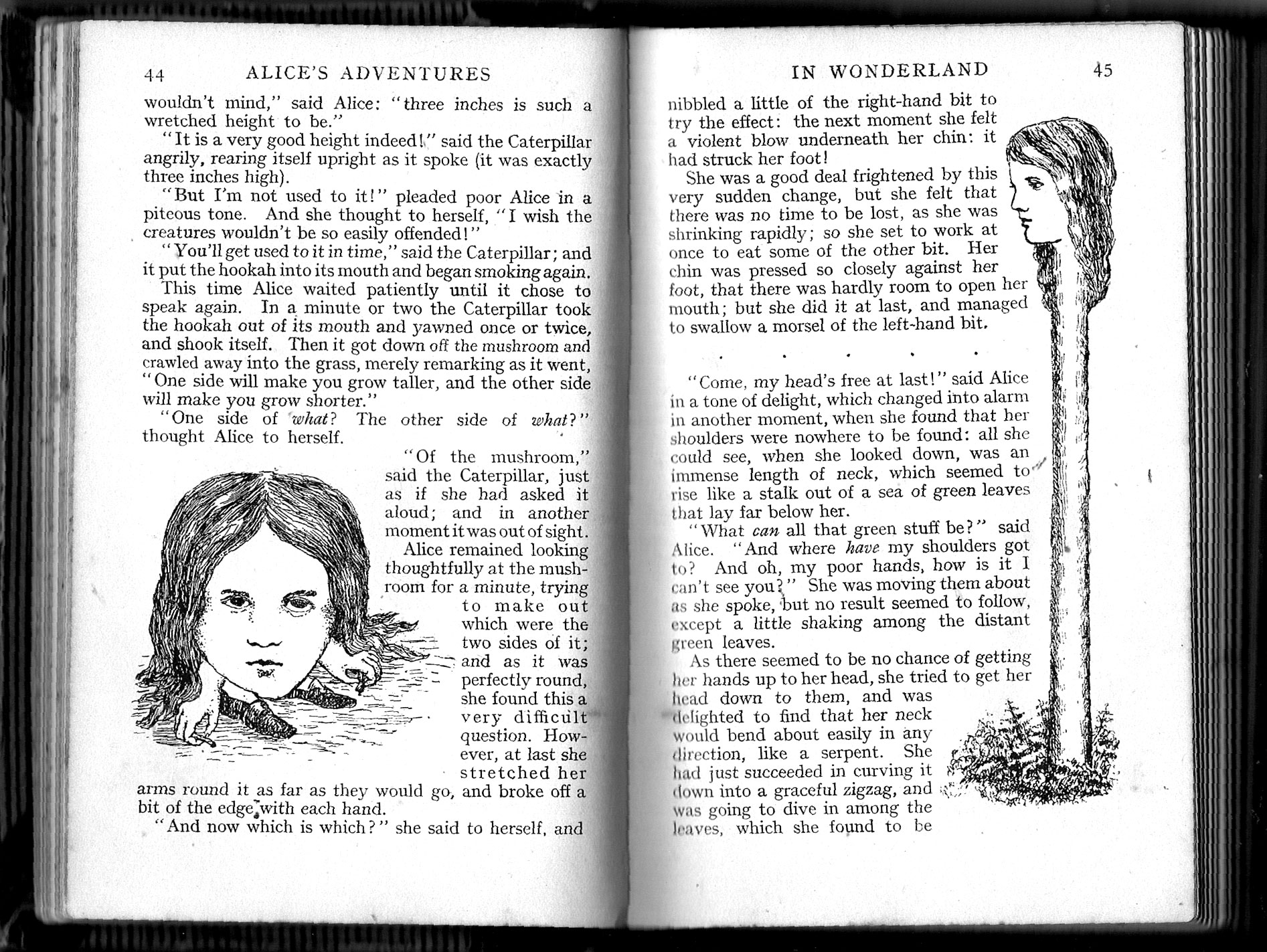

Say “Alice in wonderland”, and the image that comes to mind (well, at least in the generations that used to read books) is a little girl in a tidy Victorian knee-length puffed sleeve dress with a pinafore, and long blond hair – the girl in the image at right. This comes from the famous illustrations by John Tenniel, a successful professional illustrator that Carroll retained to illustrate the book. The illustrations by Tenniel became iconic, although they bear no resemblance to

Say “Alice in wonderland”, and the image that comes to mind (well, at least in the generations that used to read books) is a little girl in a tidy Victorian knee-length puffed sleeve dress with a pinafore, and long blond hair – the girl in the image at right. This comes from the famous illustrations by John Tenniel, a successful professional illustrator that Carroll retained to illustrate the book. The illustrations by Tenniel became iconic, although they bear no resemblance to  And then there is a different Alice altogether, the one envisioned by Carroll himself and found in the illustrations he drew by his own hand for the handwritten draft of the book, “Alice’s adventures underground”. I have a book showing these, and the comparison is interesting. Here, for example, is the same picture of Alice holding the golden key to the tiny door behind the curtain at the bottom of the rabbit hole. No blond hair, no fancy clothing.

And then there is a different Alice altogether, the one envisioned by Carroll himself and found in the illustrations he drew by his own hand for the handwritten draft of the book, “Alice’s adventures underground”. I have a book showing these, and the comparison is interesting. Here, for example, is the same picture of Alice holding the golden key to the tiny door behind the curtain at the bottom of the rabbit hole. No blond hair, no fancy clothing.

One of the most famous sculptures made in Israel is “Nimrod”, created in 1939 by Itzhak Danziger.

One of the most famous sculptures made in Israel is “Nimrod”, created in 1939 by Itzhak Danziger.